How soaring interest costs push global debt past $100trn

BY GODWIN ANYEBE

Global debt has surged beyond $100 trillion, driven by soaring interest costs that are making borrowing more expensive for governments and corporations. Nearly half of OECD and emerging market government debt will mature by 2027, forcing nations to refinance at significantly higher rates, straining budgets and limiting future spending.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) confirmed the staggering debt level on Thursday, warning that borrowing costs have reached their highest point in two decades. Interest payments have climbed to 3.3 per cent of GDP across OECD member states—exceeding what many countries spend on defence.

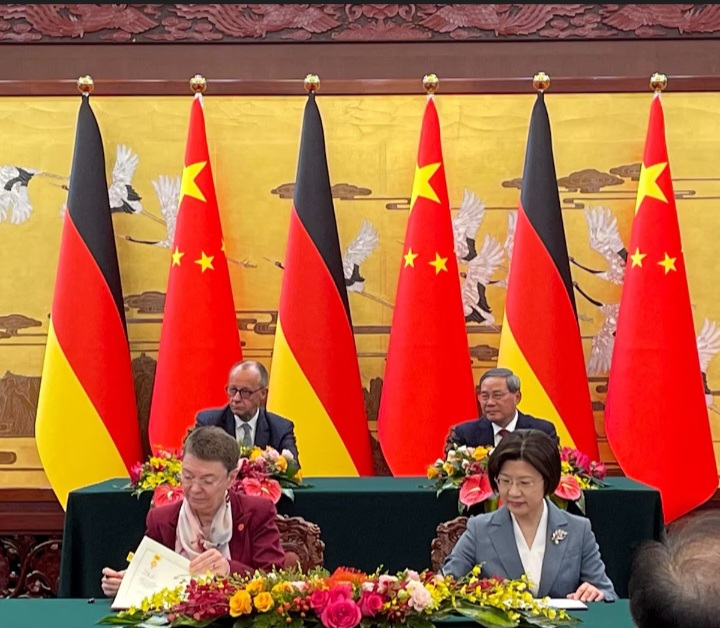

Governments now face tough choices as cheap debt from the pre-2022 era disappears. With rising expenses for infrastructure, military budgets, and the green energy transition, higher borrowing costs could squeeze economic growth. Germany, for instance, has approved major infrastructure investments while backing an EU-wide push for increased military spending, compounding financial pressures.

While interest rates may decline, debt remains costly. The OECD cautioned that borrowing would stay expensive because older, low-rate loans are being replaced by high-interest debt. “This combination of higher costs and higher debt risks restricting capacity for future borrowing at a time when investment needs are greater than ever,” the report stated.

READ ALSO: Court order preventing Ibok-Ete resuming is fake, says Aide

Nearly half of all OECD and emerging market government debt—along with one-third of corporate bonds—will mature by 2027, requiring trillions in refinancing. For low-income economies, the risk is even greater. Over half of their government debt is due within three years, with more than 20 per cent maturing this year. Without refinancing, default risks loom large.

The OECD’s head of capital markets and financial institutions, Serdar Celik, stressed the need for responsible borrowing. “If they manage this properly, we are not worried. But if they continue piling on expensive debt without boosting economic productivity, financial pressures will escalate.”

Since 2008, corporations have taken on more debt, yet much of it has gone into refinancing and shareholder payouts rather than productive investment. The OECD warned that this strategy is unsustainable. For emerging markets, strengthening local capital markets could reduce reliance on foreign-currency debt, which has become increasingly costly.

Dollar-denominated borrowing rates have jumped from 4 per cent in 2020 to over 6 per cent in 2024, with high-risk, junk-rated economies now paying more than 8 per cent. Many of these nations struggle to tap domestic savings, leaving them vulnerable to external financial shocks.

The OECD also highlighted the financial strain of achieving net-zero emissions. At current investment levels, emerging markets outside China could face a $10 trillion funding gap by 2050. If governments attempt to finance these green initiatives alone, debt-to-GDP ratios could rise by 25 percentage points in advanced economies and 41 points in China. If private investors take the lead, corporate debt in energy markets outside China would need to quadruple by 2035.