The Ochanya Ogbanje Case and Nigeria’s Rape Culture

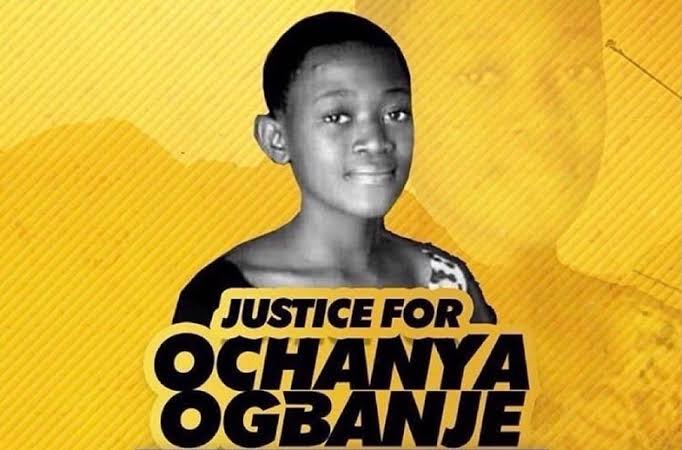

I stood in the scorching Abuja sun in 2018, holding a placard that read “#JusticeForOchanya.” Around me, hundreds of voices rose in unison, demanding accountability for a child whose suffering should have shaken our nation to its core. Seven years later, Ochanya Ogbanje’s killers still walk free, and her story has become a mirror reflecting everything broken about our relationship with sexual violence.

Ochanya died at thirteen after being sent to live with her aunt, Felicia Ogbuja, seeking education. Instead, from age eight to thirteen, her aunt’s husband, Andrew Ogbuja, a lecturer at Benue State Polytechnicand his son Victor raped her. The assaults were so brutal that Ochanya developed Vesicovaginal Fistula, leaving her incontinent, her body destroyed by men who should have protected her. In April 2022, Justice Augustine Ityonyiman of the Benue State High Court acquitted Andrew Ogbuja of all charges, citing “technical” failures. Despite video evidence of Ochanya narrating her ordeal, the judge lamented that “it is regrettable that the deceased could not tell her story before she died.” She did tell her story. Nigeria’s justice system just chose not to listen. Victor fled and remains free, reportedly pursuing a music career in Lagos.

The statistics are damning. One in four Nigerian girls experiences sexual violence before age eighteen. In a 2014 national survey, 70% of female victims reported multiple incidents, yet only 5% sought help.Between 2019 and 2020, Nigeria recorded just 32 rape convictions. In Lagos State, out of 283 child sexual assault cases reported in 2011, only 10 resulted in conviction. These aren’t just numbers. They’re human beings. They’re Ochanya, multiplied by millions, their screams absorbed into a culture that would rather silence them than confront our collective sickness.

We cannot discuss Nigeria’s sexual violence crisis without addressing child marriage; state-sanctioned pedophilia dressed in cultural clothing. Approximately 44% of Nigerian girls are married before age eighteen, with 22 million child brides. In some parts of the country like Bauchi State, that figure rises to 73.8%. While the law sets the age of consent at eighteen for rape cases, this doesn’t apply within marriage. We’ve created a loophole that allows adult men to legally rape children, and we call it tradition. We call it anything except what it is: sustained sexual abuse of minors.

Nigerian women who dare to speak about sexual assault face violence; social, psychological, legal. Women who publicly name their rapists face defamation lawsuits and retaliatory police investigations. When you report rape in Nigeria, you’re blamed for what you wore, where you went, what you drank. Many women including me don’t report sexual assault; I work with sexual assault victims and still I do not report the many cases of sexual assault that have happened to me because I‘ve watched others be torn apart for speaking up. Because weknow the police might demand bribes. Because in a nation where only 56% of married women feel they can say no to sex with their husbands, consent is a foreign concept.

This rape culture doesn’t stay within our borders. Nigerian men who grow up where sexual violence is normalized take that mindset abroad. In the UK, Nigerian nationals were among those responsible for ten rape convictions in recent data. Tosin Dada and Solomon Adebiyi face life imprisonment after conviction for multiple rapes. In the United States, Samuel and Samson Ogoshi were extradited from Nigeria in 2023 for sexual exploitation resulting in death. These aren’t isolated incidents, they’re patterns showing men who believed they could abuse women with impunity discovering that other legal systems actually prosecute sexual violence.

To be a Nigerian woman is to navigate life knowing your body is considered public property. That your “no” is negotiable. That if violated, you’ll shoulder the blame. It means watching your government create laws it refuses to enforce. It means seeing rapists become senators, pastors, professors; respected community members whose violence is an “open secret.” It means watching Ochanya’s case drag through courts for years, only to end with her rapist’s acquittal and her aunt receiving five months for negligence. It means knowing that multiple systems failed this child and then failed her again in death.

We must demand systemic change. Nigeria needs a comprehensive sex offender registry across all states. We need specialized sexual assault courts with trained judges who understand trauma. We need mandatory sexuality education teaching consent and bodily autonomy. We need increased funding for Sexual Assault Referral Centers, 50centers for 200 million people is obscene. We need expanded DNAforensic capacity.

Every time we excuse child marriage as “tradition,” we’re complicit. Every time we question what a rape victim was wearing instead of why her rapist felt entitled to her body, we choose violence. Ochanya Ogbanje should be twenty years old today. She should be in university, dreaming dreams, becoming who she was meant to be. Instead, she’s dead, killed by those entrusted with her care, failed by every institution that should have saved her, and denied justice even in death.

Her killers are free. Andrew Ogbuja is a lecturer. Victor Ogbuja reportedly pursues music in Lagos. Their sister Winifred Ogbuja is on social media making very public posts about their fun family life amid this injustice. Seven years later, I’m still holding this placard, asking: how many more Ochanyas will it take? How many more girls must die before we admit that our culture is killing them? The answer cannot be one more.

#JusticeForOchanya isn’t just about one girl. It’s about choosing what kind of nation we want to be. Right now, we’re choosing violence. It’s time to choose differently.

Ndi Kato is a political analyst, commentator and gender advocate challenging the systems that shape governance and social progress