Citizens, Not Customers: A Lesson in Self Awareness for the Nigerian Police

On October 9, 2025, the Nigeria Police Force posted a message on their social media pages that read, “Yes, you – our esteemed customer, we celebrate you.” It was part of a promotional graphic for Customer Service Week. The post might have been intended as lighthearted public relations, but to many Nigerians, it exposed the deep and troubling disconnect between the police and the public they are meant to serve.

In most countries, calling citizens “customers” of the police would sound strange but harmless. In Nigeria, it feels offensive. The Nigerian Police Force has become notorious for its transactional approach to law enforcement. The phrase “customer” echoes a bitter truth; Nigerians often pay for services they should receive as a right. Bribes are demanded at checkpoints. Officers collect “bail fees” even though bail is officially free. Many police officers have long treated Nigerians not as citizens to protect but as sources of personal revenue.

Nigeria’s corruption statistics make this point undeniable. According to the Afrobarometer 2023 survey, 73% of Nigerians believe that most or all police officers are corrupt, the worst rating for any public institution in the country. Only 15% of citizens say they trust the police.

Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked Nigeria 140th out of 180 countries, with a score of 26 out of 100, among the lowest in the world. The police consistently feature at the bottom of national integrity rankings, alongside customs and local government offices.

The irony of the “customer appreciation” tweet is sharpened by daily reality. A driver stopped by officers in Lagos or Port Harcourt knows to keep cash on hand, not for tolls, but for “settlement.” Citizens across the country speak of harassment, intimidation, and extortion. Those who resist are sometimes assaulted or detained without cause. The most extreme examples have been deadly.

The now disbanded Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) was accused of torture, illegal arrests, and extrajudicial killings. The #EndSARS protests in 2020 were a national cry for accountability. Although the unit was dissolved, many Nigerians feel that the culture of abuse remains intact under different names.

It would be unfair to say that every officer is corrupt. Many risk their lives in difficult conditions. The problem is systemic. Poor welfare, low salaries, and lack of equipment push officers toward extortion as a means of survival. A recruit earns less than ₦80,000 a month, often without proper accommodation. Patrol vehicles are poorly maintained, stations are underfunded, and training is minimal. In this context, corruption is not simply moral failure; it has become institutionalized survival.

Over the years, various police leaderships have promised reform. Former Inspector General Ibrahim Idris introduced community policing initiatives. Mohammed Adamu, who succeeded him, spoke of modernization and accountability. Usman Alkali Baba emphasized digital records and personnel vetting.

The current Inspector General, Kayode Egbetokun, has repeatedly said he intends to rebuild trust through professionalism and moral reorientation. The establishment of the Police Trust Fund and the passage of the Nigeria Police Act 2020 were supposed to mark turning points, modernizing the force and improving oversight.

However, these initiatives have barely scratched the surface. Training programs remain inconsistent. Oversight institutions are weak or politically compromised. The Police Service Commission, responsible for discipline and recruitment, often clashes with the Inspector General’s office, creating confusion about authority and accountability. Funding for reform rarely reaches divisional levels. Patrol officers, the face of the force, remain underpaid and poorly supervised.

The result is what analysts describe as “window dressing”, reform in language but not in culture. Public relations campaigns replace genuine reform. Uniform changes are announced while the behavior of officers remains the same. The police maintain social media accounts that trade in cheerful graphics, hashtags, and holiday greetings, but avoid honest engagement with the public. The “customer” tweet is not just an error in wording; it is a symptom of a deeper lack of institutional self awareness.

To move forward, reform must focus on both accountability and culture. Nigeria needs a police system that is transparent, properly funded, and community oriented. First, oversight must be strengthened. Internal disciplinary units should publish data on complaints, sanctions, and dismissals. Independent civilian review boards with investigative powers should be established to handle serious misconduct cases.

Second, welfare must be prioritized. Officers who are well paid and adequately housed are less likely to rely on illegal income. Training should focus on human rights, de-escalation, and empathy, not just weapon handling. Recruitment should emphasize education and psychological fitness, not political connection.

Third, technology should be leveraged. Body cameras, digital records, and transparent case tracking can reduce abuse and strengthen accountability. Data transparency must become routine, not an exception. All these are of course, subject to better funding for the police.

Finally, reform must be citizen-centered. A citizen-friendly police force begins with a shift in mindset; the Nigerian public is not “customers” but partners in security. Every citizen has a right to safety and dignity. Policing must be service, not business.

Nigeria’s police can change. Other countries have done it. The transformation of the Rwandan and Kenyan police over the last decade shows that sustained investment, leadership, and accountability can rebuild public trust. But change requires honesty. As long as the police continue to celebrate “customers” while citizens experience harassment and fear, reform will remain a slogan.

The Nigeria Police Force has the opportunity to rewrite its story. It must start by recognizing that the people it calls “customers” are not buyers of safety, but owners of it; the police owe them service. Until that shift happens, trust will remain out of reach, and public relations tweets will continue to sound hollow.

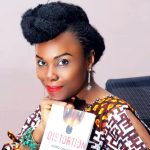

Ndi Kato is a political analyst, writer, and advocate for women’s inclusion in governance. She is the founder of the Dinidari Foundation and has served as a presidential campaign spokesperson; the first woman and youngest person to hold that role in Nigeria. Her columns focus on governance, gender, and social development, bringing sharp insight and accountability to national discourse.