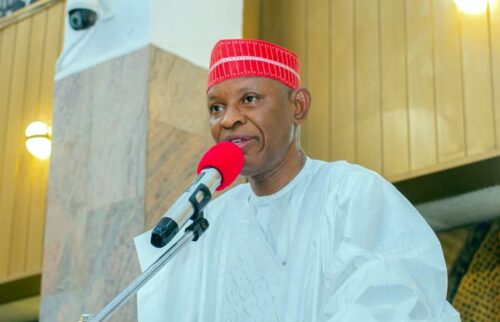

For Gov Abba Kabir Yusuf, A Risky Gamble

By Sheddy Ozoene

Since the middle of 2025, when rumours first began to circulate that Kano State Governor, Abba Kabir Yusuf, was contemplating a break with the Kwankwasiyya Movement that brought him to power in 2023, many dismissed the speculation with a wave of the hand.

Abba was not only the favoured godson of Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso; he shared a personal relationship with the former governor that dated back more than four decades when both men worked together as civil servants in Kano.

That bond was further cemented when Abba married into the Kwankwaso family, positioning himself strongly as the political heir to a man who today commands the loyalty of millions of Kano’s commoners—the talakawa.

It was a huge inheritance, and the pressure that came with it was immense. Since becoming governor in 2023, the All Progressives Congress (APC), which controls the federal government, has mounted sustained pressure on him. Simultaneously, voices within Yusuf’s inner circle repeatedly highlighted Kwankwaso’s overbearing influence and urged the governor to “run on his own steam.”

But on January 23, 2026, the governor took the plunge. He abandoned the Kwankwasiyya Movement, severed ties with his long-time political benefactor, left the New Nigeria People’s Party (NNPP) on whose platform he was elected governor, and joined the ruling APC.

He did not go alone. He crossed over with dozens of former Kwankwasiyya loyalists: all but four members of his State Executive Council, all members of the State House of Assembly, eight National Assembly members, and all 44 local government chairmen.

In its chequered political history, Kano has witnessed major upheavals, but none compares to the scale and seismic nature of this recent realignment. Beyond the Rimi–Aminu Kano schism of 1983—which had clear ideological foundations—no rupture has occurred on this magnitude. The verdict, even at this early stage, is that Governor Abba Yusuf, egged on by outsiders and driven by his own personal ambitions, has taken the wrong step at the wrong time.

Beyond the tired argument of “taking Kano to the centre,” Yusuf has offered no convincing justification for a move so drastic that it now threatens to define—and possibly derail—his entire political future. His party was not in any overwhelming crisis, notwithstanding claims to the contrary.

There was no ideological face-off in the Aminu Kano/Abubakar Rimi mould. There was no visible rupture in his relationship with Kwankwaso that endangered his re-election prospects in 2027. If one discounts persistent rumours that enormous financial inducements often accompany the defection of opposition governors to the APC, the only plausible explanation for Yusuf’s move is the lure of federal might.

The argument that Kwankwaso was overbearing in his dealings with the governor carries little weight. Their relationship has always been that of godfather and godson. If Abba needed Kwankwaso to achieve his own political aspirations, it was inevitable that such a relationship would come with its own constraints. And if alignment with federal power was indeed the motive, it bears repeating that federal might has never been the currency of Kano politics. In many instances, it has been antithetical to its spirit.

Kano’s political culture is far more sophisticated. It is anchored in a populist philosophy rooted in the protection of the talakawa. Historically, it has been suspicious of power concentrated at the centre—especially when federal policies, like those of the present administration led by Bola Ahmed Tinubu, are perceived as elitist rather than egalitarian. In such circumstances, rebellion—not conformity—has often been Kano’s political reflex.

For a politician who rose through the Kwankwasiyya Movement—a movement inspired by the radical populism of Mallam Aminu Kano, the undisputed champion of the common people—Yusuf’s defection is not merely ironic; it is ideological apostasy. Little wonder that many in Kano already regard his action as betrayal.

But does a split with Kwankwaso necessarily translate into a departure from Kano’s progressive politics and alignment with the talakawa? To a large extent, it is perceived so. Over the years, Kano politics has almost always revolved around one dominant figure at a time, and today that figure is Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso. He may have his personal shortcomings, but he still commands the crowd that matters most in Kano politics. Whether or not Yusuf continues to don the red cap that symbolises Kano’s progressive tradition is, ultimately, beside the point.

Perhaps Yusuf failed to consult history. Had he done so, he might have recalled the fate of men who abandoned their ideological roots and paid dearly for it. Foremost among them is the cautionary tale of Muhammadu Abubakar Rimi, the charismatic governor of Kano State in the early 1980s.

Rimi fell out with his political mentor, Mallam Aminu Kano, during his first term over ideological differences, political strategy, and internal power struggles within the People’s Redemption Party (PRP). The disagreement split the party into two factions. While Mallam Aminu retained the Tabo (traditional) wing, Rimi led the Santsi (radical) wing out of the PRP and into the Nigerian People’s Party (NPP). In an unprecedented move, Rimi resigned both from the PRP—the platform on which he was elected—and from office as governor before contesting the 1983 election on a new platform.

The people of Kano were clearly impressed with his principled decision to resign; but they also interpreted his action as betrayal. They responded with the harshest political punishment available: a crushing defeat at the hands of Alhaji Sabo Bakin Zuwo of the PRP in the 1983 election.

Rimi and the Santsi group never recovered from that misadventure. Until his death in April 2010, his political career remained a shadow of what it once promised.

Rimi’s story has since become a standing reference point in Kano politics—invoked whenever ambition appears to eclipse reason, loyalty to the talakawa, and the political principles that define Kano state. It should have served as a lesson for Governor Abba Yusuf, who did not even possess the principled conviction Rimi showed by resigning his office. If Rimi failed to convince the people in 1983, how does Yusuf intend to convince them that joining the Tinubu bandwagon—largely driven by the quest to secure a second term for the President in 2027—has become an overriding imperative?

The fact is that Abba was in too much of a hurry to ‘extricate’ himself from Kwankwaso. While not totally averse to the APC move, Kwankwaso had insisted on certain conditions before the Kwankwasiyya group defects. It turned out a stab in the back that Abba would suddenly team up with Alhaji AbdullahI Umar Ganduje, another ally-turned rebel, to strike a deal with the APC at Kwankwaso’s back. He should first have asked Ganduje where he ended up with his own Gandujjiyya Movement.

The fact that Yusuf pulled a large number of elected representatives into the APC may ultimately prove inconsequential. It merely echoes 1983, when Rimi led a similar exodus, yet only one member of the House of Assembly who followed him was re-elected.

Abba Kabir Yusuf may believe that federal backing will shield him from a fate similar to Rimi’s. Perhaps. Much will undoubtedly be done to cushion his landing in the APC and to present his defection as beneficial to Kano. The recent promise of a Kano Metroline project—purportedly valued at ₦1 trillion, despite its conspicuous absence from this year’s federal budget—is already being paraded as evidence of federal goodwill. But history tells us that Kano voters are not easily impressed by spectacle.

For a man who has spent decades in Kano politics, Yusuf should know this better than most others who advised him to take this gamble. In Kano, power may flow from Abuja, but legitimacy comes from the commoners—and they have never failed to pass judgment when the moment arrives. Yusuf has, indeed, come full circle, which makes his current gamble all the more puzzling—and potentially perilous.